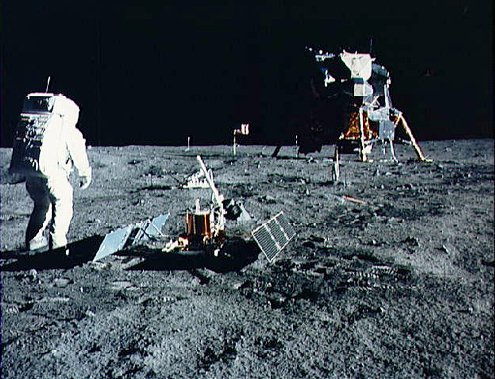

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was one of several Westerns to emerge in 1969, a year in which the United States reached towards an entirely new frontier with the moon landing. CASSIDY treats the nostalgia for the old Western frontier with a humor that played with varying levels of success in 1969.

The movie was given a platform release, with the limited release occurring September 23, and the American wide release one month later. At $6M, its budget was nearly 20 times that of EASY RIDER (Hopper, USA, 1969)– but at $49M in US rentals, its profit was two and a half times its counterpart’s. Adjusted for inflation, its US gross of $100M ranks among the 100 highest-grossing movies of all time.

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was a movie of the Hollywood establishment. Starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman, who was riding high on the success of COOL HAND LUKE (Rosenberg, USA, 1967), the film employed studio and location shooting, a tremendously successful score by Burt Bacharach, and expensive special effects to impress audiences worldwide. For the Academy, at least, it worked: the film was nominated for seven Oscars (including Best Picture) and won four: for Best Cinematography, Best Original Score, Best Original Song and Best Original Screenplay. In addition, it swept the BAFTAs and also took home a Golden Globe and a Grammy. Added to the National Film Registry in 2003, it is number seven on the AFI Ten Best Westerns list.

In spite of its mainstream critical acclaim, BUTCH CASSIDY did not play well among more serious and scholarly critics. New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby stated in 1969 that the film “did not succeed”, while Stephen Farber, writing for Film Quarterly, goes so far as to call the movie “offensive”. Roger Ebert blames CASSIDY’s flaws on the “millions of dollars that were spent on ‘production values’ that wreck the show”; Roger Corliss describes it as “a meticulous Boliviazation of Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a sort of second-generation rebel – slick, handsome, a lot like mom and dad but a little too fat and self-conscious.” In the most forgiving review to be found in Film Quarterly at the time, Dennis Hunt calls BUTCH CASSIDY “a playful, effervescent Western that has been tailored to the tastes of the Pepsi generation.” The film is a neat counterpart to EASY RIDER, which achieved serious critical acclaim in spite of its financial limitations and roots outside the studio system. In contrast, CASSIDY suffers precisely because of its studio dollars and high production values. It is another angle from which to view the sea change that took place in the American film industry at the end of the 1960s.

Unlike EASY RIDER, BUTCH CASSIDY was filmed entirely after the 1968 DNC, and mostly after the 1968 presidential election. Perhaps that accounts for its more conservative, conformist industrial context. However, in a 1970 interview, Oscar-winning cinematographer Conrad Hall responded to the question of whether he thought people were serious enough about revolution to go into the streets, “I think so. I didn’t think so a year and a half ago, but I think so now.” Again, the uncertain climate of 1969 manifests in conflicting visions of the direction of American culture – away from revolution on the industrial side, but towards it in terms of vision or mood.

Critics at the time remarked that BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was a film very aware of being at the end of an era. Writes Farber, “I suppose what drew [screenwriter] Goldman to the material was the sense that these men were the last Western bandits”. Similarly, Vincent Canby describes it as “the last exuberant word on movies about the men of the mythic American West who have outlived their day.” Like the motorcyclists of EASY RIDER, Butch and Sundance are the last hope of a rebellion that will be put down.

In his article American Cinematic Form, Richard Kenney eloquently describes this sense of impending doom:

Even in the atmosphere of nostalgic humor, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid cannot live as anachronisms beyond their Southwestern time; neither can the Wild Bunch hope to escape baroque death in an age of Verdun. Cassidy, the Kid, and the Bunch didn’t die because they were bad men, or even violent men – they were good men, or good enough, and they each died in an astonishing apocalypse of gunfire, under a far greater violence than they ever would have generated by themselves. The laws and soldiers and societies had become more dangerous than the outlaws.

According to Dennis Hunt, the film’s antagonists are “a ponderous symbol of progress closing in to snuff out the desperado’s way of life”. Each of these critics picks up on the sense present both in CASSIDY and in EASY RIDER that the outsiders or outlaws have become the last hope of society, and that nominally “respectable” people will be its downfall.

The message of BUTCH CASSIDY is of course complicated by the fact that it was deeply rooted in the very system of respectability it symbolically critiques: it was a big studio blockbuster, multiple Oscar-winner, the ultimate insider. However, the fact that its message is so similar to EASY RIDER’s, although the production processes were nearly opposite, demonstrates the pervading mood of 1969, a mood that is familiar today as we have watched the most respected businessmen of our era lead us to the worst economic crisis of the last several generations, and our top politicians condone practices held for decades to be barbarous. The last frontiers of America have been explored and exploited, and we are left with the sense that we will have to turn elsewhere, or give up.

At the Northwest Film Forum, with EASY RIDER: January 9-15, 2009, 8:30pm

1 comment:

I love BCATSK!

My favorite scenes are the bicycle scene, and of course the final shootout. What do you think of the symbolism of the finale?

Post a Comment