Sunday, March 15, 2009

I started a tumblelog.

P.S. This also means that this place is probably now defunct - but I'll keep it alive for sentiment's sake.

Saturday, March 14, 2009

Save Arts & Culture in King County!

Friday, January 16, 2009

Little Sis - "An Involuntary Facebook of Powerful Americans"

To check out the site, go here. To sign up to contribute to it, go here. To familiarize yourself with what the site is supposed to do and why the heck it matters, go to the site's "purpose" page, read the text pasted below, or, if you've got some time on your hands and want the deluxe version, read this very eloquent post on the site's blog by LittleSis's E.D., Matthew Skomarovsky, about "Why LittleSis Matters". (It's long but well worth the read).

********************************

LittleSis brings transparency to influential social networks from Wall Street to Washington. The site is an involuntary facebook of powerful Americans, collaboratively edited by an online community of analysts.

Profile pages catalogue important relationships between politicians, CEOs, financiers, lobbyists, and other important folks. By tracking everything from board memberships to campaign contributions, family ties to government contracts, LittleSis opens up elite networks for public inspection. Why do this? Because whether you like them or not, they play a crucial role in shaping public policy; they make decisions that affect our lives in profound ways.

LittleSis is an ambitious experiment in "crowdsourcing" transparency; though the site's core data sets are built and maintained by the LittleSis team, anyone can sign up to become an analyst and contribute (well-sourced) information.

Unlike more traditional wikis, LittleSis is optimized for tracking relationships. Add a relationship between two people and it shows up on both profile pages. For example, Eric Holder and Valerie Jarrett are close. This makes it a good tool for tracking power and influence.

Structured data of this nature allows for some interesting analysis. Go to the "interlocks" tab on each profile and you can see a list of shared organizational affiliations. For instance, oil companies appear to dominate the Augusta National Golf Club. Go to the "giving" tab on each profile, and you can get an interesting window onto the giving patterns for the organization or individuals you're looking at. People on the Obama Transition Economic Agency Review Team seem to have split their contributions between Obama and Hillary.

A disclaimer: since LittleSis is a beta and just starting to make its way out into the world, there are gaps and holes in the data and application. Don't use it as a definitive resource, but consider its potential, especially as people begin contributing more information to the site.

The site is a project of the Public Accountability Initiative (public-accountability.org) a research and educational 501(c)3 focused on corporate and government accountability. We have backgrounds in investigative research, political action, and web development, much of it from within the labor movement (SEIU, Harvard Living Wage, Freelancers Union). The site has been supported by Sunlight Foundation, a leader in the government transparency movement.

In case you're wondering about the name: "Big Brother" is commonly used to describe a situation where the electronic eyes of the powers that be are vigilantly watching citizens for misbehavior. "LittleSis" is a website where the electronic eyes of citizens are vigilantly watching back.

Are you a journalist or blogger? An activist? A politics junkie? A concerned citizen? Are you tired of shaking your fist at the powers that be without letting them know you're watching?

Sign up now to become a contributing analyst at LittleSis. Once you receive the proper credentials, you will be able to edit the profile pages of your favorite (or least favorite) fat cats.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

1969: BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID (Penn, USA, 1969)

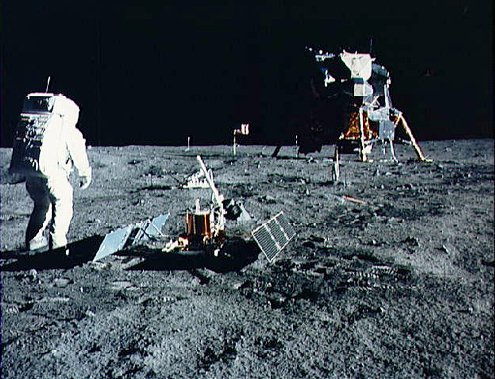

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was one of several Westerns to emerge in 1969, a year in which the United States reached towards an entirely new frontier with the moon landing. CASSIDY treats the nostalgia for the old Western frontier with a humor that played with varying levels of success in 1969.

The movie was given a platform release, with the limited release occurring September 23, and the American wide release one month later. At $6M, its budget was nearly 20 times that of EASY RIDER (Hopper, USA, 1969)– but at $49M in US rentals, its profit was two and a half times its counterpart’s. Adjusted for inflation, its US gross of $100M ranks among the 100 highest-grossing movies of all time.

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was a movie of the Hollywood establishment. Starring Robert Redford and Paul Newman, who was riding high on the success of COOL HAND LUKE (Rosenberg, USA, 1967), the film employed studio and location shooting, a tremendously successful score by Burt Bacharach, and expensive special effects to impress audiences worldwide. For the Academy, at least, it worked: the film was nominated for seven Oscars (including Best Picture) and won four: for Best Cinematography, Best Original Score, Best Original Song and Best Original Screenplay. In addition, it swept the BAFTAs and also took home a Golden Globe and a Grammy. Added to the National Film Registry in 2003, it is number seven on the AFI Ten Best Westerns list.

In spite of its mainstream critical acclaim, BUTCH CASSIDY did not play well among more serious and scholarly critics. New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby stated in 1969 that the film “did not succeed”, while Stephen Farber, writing for Film Quarterly, goes so far as to call the movie “offensive”. Roger Ebert blames CASSIDY’s flaws on the “millions of dollars that were spent on ‘production values’ that wreck the show”; Roger Corliss describes it as “a meticulous Boliviazation of Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a sort of second-generation rebel – slick, handsome, a lot like mom and dad but a little too fat and self-conscious.” In the most forgiving review to be found in Film Quarterly at the time, Dennis Hunt calls BUTCH CASSIDY “a playful, effervescent Western that has been tailored to the tastes of the Pepsi generation.” The film is a neat counterpart to EASY RIDER, which achieved serious critical acclaim in spite of its financial limitations and roots outside the studio system. In contrast, CASSIDY suffers precisely because of its studio dollars and high production values. It is another angle from which to view the sea change that took place in the American film industry at the end of the 1960s.

Unlike EASY RIDER, BUTCH CASSIDY was filmed entirely after the 1968 DNC, and mostly after the 1968 presidential election. Perhaps that accounts for its more conservative, conformist industrial context. However, in a 1970 interview, Oscar-winning cinematographer Conrad Hall responded to the question of whether he thought people were serious enough about revolution to go into the streets, “I think so. I didn’t think so a year and a half ago, but I think so now.” Again, the uncertain climate of 1969 manifests in conflicting visions of the direction of American culture – away from revolution on the industrial side, but towards it in terms of vision or mood.

Critics at the time remarked that BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID was a film very aware of being at the end of an era. Writes Farber, “I suppose what drew [screenwriter] Goldman to the material was the sense that these men were the last Western bandits”. Similarly, Vincent Canby describes it as “the last exuberant word on movies about the men of the mythic American West who have outlived their day.” Like the motorcyclists of EASY RIDER, Butch and Sundance are the last hope of a rebellion that will be put down.

In his article American Cinematic Form, Richard Kenney eloquently describes this sense of impending doom:

Even in the atmosphere of nostalgic humor, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid cannot live as anachronisms beyond their Southwestern time; neither can the Wild Bunch hope to escape baroque death in an age of Verdun. Cassidy, the Kid, and the Bunch didn’t die because they were bad men, or even violent men – they were good men, or good enough, and they each died in an astonishing apocalypse of gunfire, under a far greater violence than they ever would have generated by themselves. The laws and soldiers and societies had become more dangerous than the outlaws.

According to Dennis Hunt, the film’s antagonists are “a ponderous symbol of progress closing in to snuff out the desperado’s way of life”. Each of these critics picks up on the sense present both in CASSIDY and in EASY RIDER that the outsiders or outlaws have become the last hope of society, and that nominally “respectable” people will be its downfall.

The message of BUTCH CASSIDY is of course complicated by the fact that it was deeply rooted in the very system of respectability it symbolically critiques: it was a big studio blockbuster, multiple Oscar-winner, the ultimate insider. However, the fact that its message is so similar to EASY RIDER’s, although the production processes were nearly opposite, demonstrates the pervading mood of 1969, a mood that is familiar today as we have watched the most respected businessmen of our era lead us to the worst economic crisis of the last several generations, and our top politicians condone practices held for decades to be barbarous. The last frontiers of America have been explored and exploited, and we are left with the sense that we will have to turn elsewhere, or give up.

At the Northwest Film Forum, with EASY RIDER: January 9-15, 2009, 8:30pm

Sunday, November 16, 2008

1969 Begins: EASY RIDER

Gentle readers,

Gentle readers,over the next few days, weeks, or perhaps months, I will be offering here the fruits of my labor on behalf of the Northwest Film Forum as part of their 1969 series, which will take place over the course of 2009. The idea behind this program is not to present a nostalgic look back at a bygone era, so much as to use 1969 as a sociopolitical and aesthetic lens to examine our own time. Naturally, the outcome of this month's election will prove a major distinguishing factor between 1969 and 2009, but the parallels to be drawn are many, nevertheless.

The first wave of material will be essays I am composing on the first fourteen movies to be presented as part of the 1969 program. These essays have been loosely composed, and are rough and associative at best. Please be kind - but do leave comments, as I would like your engagement in the conversation to help spark ideas for new avenues of research and exploration. I begin with my work on EASY RIDER.

-alex b.

********************************************

EASY RIDER (Hopper, USA, 1969)

Given a wide United States release in mid-July, 1969, Easy Rider is often named as an exemplary film of its generation. The most problematic part of this statement is that few can agree on that generation’s identity. It was, as we have remarked, a period of transition, of schizophrenic perception and evaluation, of frightening uncertainty and terrifying expectations. Perhaps EASY RIDER is most emblematic of its filmic generation in its very contradictions and ambiguities, which range from the financial to the formal, hitting nearly everything in between.

The most obvious contradiction in the story of EASY RIDER is its critical and financial success in spite of its departure from the traditional Hollywood studio system. Its break with this system is viewed to this day as a forerunner of the Hollywood Renaissance. Produced on a shoestring budget of about $350,000, the film nonetheless netted $19M in the United States, grossing $60M worldwide. Nominated and rejected for two Oscars, EASY RIDER took the First Film Prize (Prix de la premiere oeuvre) at Cannes. Both its financial and (international) critical success seemed to be a slap in the face of the cinematic establishment, which tended to base expectation of return on financial investment. As Stephen Farber writes in the 1969 article “End of the Road,” the summer of 69 marked a turning point in the American film industry, when blockbusters failed and most top grossing films, including EASY RIDER and MIDNIGHT COWBOY, were low-budget independent productions.

Equally ambiguous and contradictory is the story of EASY RIDER’s pop soundtrack (the music also serves to tie the film to its cultural era). Though not the first film to use a pop soundtrack, it was perhaps the first to use it to such great effect. The myth of EASY RIDER is that with no money for an original score, Dennis Hopper played the a rock ‘n’ roll scratch track to accompany the film’s first studio screening. The studio executives allegedly loved it so much that they insisted it be kept on. Given that the rights for the music cost about $1M, or three times the film’s estimated budget, it seems doubtful that it was as spontaneous as all that, but the story exemplifies one of the film era’s defining characteristics, namely a desire to believe in the mythos of film-auteur-as-maverick, even when the “maverick” actions were only made possible by system dollars.

It is possible that the film’s defiant, sometimes naïve railing against “the system” and “the man” stem from its filming dates. Though released in July 1969, EASY RIDER was filmed from March-May 1968, before the assassination of RFK and the Chicago convention, two events commonly named in discussions of the downfall of 1960s optimistic idealism. The film centers on what Roger Ebert called “specific rejection of the establishment (by which is meant everything from rednecks to the Pentagon to hippies on communes)” in his original 1969 review. Perhaps it was the election of Richard Nixon,

which distinguishes 1969 from 2009 perhaps more sharply than any other event, but 1969 onwards was a period remarkable for its return to conformity, not rejection of the establishment. In EASY RIDER, we can see the last vestiges of the 1960s’ rebellion. At the same time, the film, edited and released in 1969, ends with the cynicism that would come to characterize the 1970s.

which distinguishes 1969 from 2009 perhaps more sharply than any other event, but 1969 onwards was a period remarkable for its return to conformity, not rejection of the establishment. In EASY RIDER, we can see the last vestiges of the 1960s’ rebellion. At the same time, the film, edited and released in 1969, ends with the cynicism that would come to characterize the 1970s. In 1969, Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times that “Hopper, Fonda and their friends went out into America looking for a movie and found instead a small, pious statement (upper case) about our society (upper case), which is sick (upper case).” Canby claims that EASY RIDER is “pretty but lower case cinema”; regardless, the landscape from which it sprang is one that is familiar today, and the product perhaps something from which we can learn.

In 1969, Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times that “Hopper, Fonda and their friends went out into America looking for a movie and found instead a small, pious statement (upper case) about our society (upper case), which is sick (upper case).” Canby claims that EASY RIDER is “pretty but lower case cinema”; regardless, the landscape from which it sprang is one that is familiar today, and the product perhaps something from which we can learn.Perhaps the most significant contradiction in EASY RIDER’s terms was that in spite of its groundbreaking aspects, it was also deeply rooted in the American film tradition. Writing in 1971 of Westerns in his article American Cinematic Form (published in Film Quarterly), Richard Kenney states,

“Cowboys made the American romance of freedom and violence. Americans have always been a violent people, and they admire the rugged individualist, pioneer spirit, the loner and the open road…EASY RIDER is a romance of the open road.” This connection between EASY RIDER and the Western is commonly drawn; Roger Ebert, too, uses the Western as a tool to understand EASY RIDER in his original 1969 review. The American obsession with the frontier is still with us, and was certainly characteristic of 1969, with its Westerns and moon landings. EASY RIDER’s juxtaposition with BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, a much more obvious product of the Western genre, may help viewers understand the film through that lens. A glossy, high-budget production, BUTCH CASSIDY will also provide a counterpoint to EASY RIDER’s scrappy production values, as the two films demonstrate the two ends of 1969’s schizoid film continuum.

“Cowboys made the American romance of freedom and violence. Americans have always been a violent people, and they admire the rugged individualist, pioneer spirit, the loner and the open road…EASY RIDER is a romance of the open road.” This connection between EASY RIDER and the Western is commonly drawn; Roger Ebert, too, uses the Western as a tool to understand EASY RIDER in his original 1969 review. The American obsession with the frontier is still with us, and was certainly characteristic of 1969, with its Westerns and moon landings. EASY RIDER’s juxtaposition with BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, a much more obvious product of the Western genre, may help viewers understand the film through that lens. A glossy, high-budget production, BUTCH CASSIDY will also provide a counterpoint to EASY RIDER’s scrappy production values, as the two films demonstrate the two ends of 1969’s schizoid film continuum.

Saturday, August 2, 2008

The pacifist pull of W.H. Auden

On this recent evening, when I returned to Auden for the first time in several months, I stumbled across the poem James Honeyman, a poem which illustrated to me again what I loved so much about O What Is That Sound? Both works, penned in the mid-late 1930s, are indisputably political products of Auden's deep-seated pacifism in the face of the Spanish Civil War and impending Second World War. Unlike many political poets, however, Auden remains deeply invested in form, and in a prettiness of language that never bows to the ugliness of content. In fact, it is this tension, between appealing form and repulsive content, that is the key to Auden's power. James Honeyman, in particular, makes use of simply formulaic verses. Like O What Is That Sound, it disarms the reader with its tripping rhythm and attractive images (a "ten-shilling chemistry set", or a small child who sits at a party dreamily dissolving sugar in his tea), pulling said recipient toward a moment of terrifying violence, which the poem's protagonist must confront alone.

After the idyll of content and form established in the early verses, that moment of confrontation shocks the reader, takes her by surprise and abrades her sensibilities, which have been finely tuned to the peaceful opening stanzas. This switch, contained in rigorously designed verses, portrays the fiendishness of violence, and its embeddedness in society, with unsurpassed accuracy. As we know all too well, violence is not a breaking of societal forms or norms, but the result of conforming to them and pursuing them to their natural conclusion. If we do not pay attention, we too must die (and we know why) by Honeyman's N.P.C.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

48 HOUR FILM CHALLENGE THURSDAY 6:30PM

If you're in the Seattle area, come check out films made for the 48-hour film project this past weekend - especially this one. The screening is this Thursday, July 17, at the Neptune Theatre.

The address is 1303 N 45th St, Seattle.

See you there!